Like saying hello, saying goodbye is an important part of being polite. These are the most basic skills you need to have a conversation in any language, so it’s crucial that you acquire them early on.

In this article, we’ll tell you how to say goodbye in Polish in a variety of situations. For example, you’ll learn the best parting words for formal versus informal environments, how to see someone off at the airport, and how to end a phone conversation. By the time you’ve finished reading, you’ll have the perfect Polish goodbye for any situation you find yourself in. Are you ready to get your Polish up to scratch? Start with a bonus, and download the Must-Know Beginner Vocabulary PDF for FREE!(Logged-In Member Only)

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

1. The Most Common Ways of Saying Goodbye

Before we look into the more specific ways of saying goodbye in Polish, let’s discuss the simplest ways to do so. Remember that you should address people differently depending on whether the situation is formal or informal.

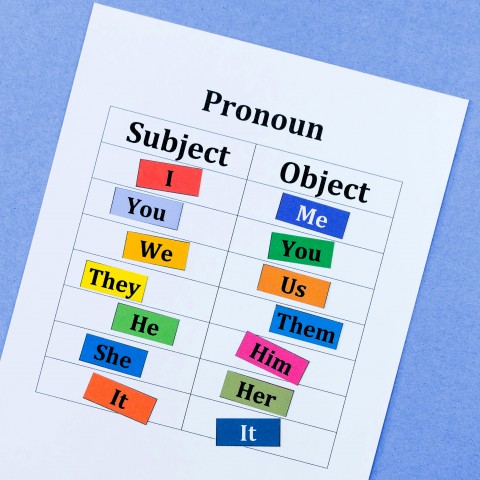

Formal verb forms use the third person singular and the words Pan (“Mister”) and Pani (“Ma’am”). For example, to ask “What’s your name?” in a formal manner, you would say: Jak ma Pan/Pani na imię?

The informal verb forms use the second person singular. To ask “What’s your name?” in an informal manner, you would say: Jak masz na imię?

So how do these rules apply to Polish goodbye phrases? Let’s find out!

A- Goodbye in Polish (Informal)

The most common informal way of saying bye in Polish is: Cześć! Note that this word is also used for saying hello. (If you want to learn more about this topic, you can check out our lesson “Saying Hello No Matter the Time of Day in Polish.”)

Cześć is very versatile, and you can use it to say goodbye when you’re leaving any informal situation. We also use a variation: No to cześć!

Both Cześć! and No to cześć! are used with either the nominative case (mianownik) or the vocative case (wołacz):

- Cześć, Ania! – “Bye, Ania!” (nominative, mianownik)

- Cześć, Aniu! – “Bye, Ania!” (vocative, wołacz)

B- Goodbye in Polish (Formal)

The most common formal goodbye in Polish is: Do widzenia! This phrase is used in all kinds of formal situations, such as when you’re leaving a corner shop, post office, or doctor’s office. It’s often accompanied by Dziękuję! (“Thank you!“) if a service was provided:

- Oto Pani/Pańska reszta. – “Here’s your change.” (to a man and a woman, respectively)

- Dziękuję, do widzenia. – “Thank you. Goodbye!”

We can also say Dobranoc Panu/Pani to wish someone a good night’s rest.

Practice your pronunciation of Do widzenia! whenever you can. Try to use this phrase in real life, even if the rest of your conversation is in English. Practice makes perfect!

2. Specific Ways of Saying Goodbye in Polish

There are many Polish language goodbyes that you can use in more specific situations.

When you’re formal with someone, you simply don’t have certain conversations with them. This is why Do widzenia! is your go-to goodbye in formal contexts.

Keep reading to find out how to say goodbye in Polish when the situation is informal!

A- Alternative Ways to Say Bye in Polish

Apart from simply saying Cześć! when you’re leaving a group of friends, you can also say:

- Na razie!

- Nara!

- Narka!

Each of the phrases above is equivalent to “Bye for now” in Polish. Here are a few more ways to say bye in Polish:

- Pa pa!

- Pa

- No to pa!

Make sure to memorize these expressions, as they’re very often used when speaking informally.

B- See You Later!

There are a couple of ways to say “See you” in Polish:

- Do zobaczenia!

- Do zo!

“See you later!” is Do zobaczenia później! You should only use this phrase, though, when you’re going to actually see that person later (for instance, later that day). In certain English-speaking countries, people say “See you later!” as a general farewell expression. But this is not a convention in Poland, and it’d confuse the person you say it to.

If you know when you’ll see that person next, you can say:

- Do zobaczenia jutro! (“See you tomorrow!”)

- Do zobaczenia w/we [day of the week]! (“See you on [day of the week]!”)

- Do zobaczenia w poniedziałek! (“See you on Monday!”)

- Do zobaczenia we wtorek! (“See you on Tuesday!”)

You can also use this sentence pattern with different times of day:

- Do zobaczenia wieczorem! (“See you in the evening!”)

- Do zobaczenia rano! (“See you in the morning!”)

As you can see, there are many ways to say goodbye in Polish. The more you study them, the more comfortable you’ll be having a conversation in Polish.

C- Seeing Someone Off

How do you say goodbye in Polish when you’re taking someone to the airport or a train station, where they’re about to start a long journey? Of course, you say Do zobaczenia! But there are other things that you can add, such as:

- Trzymaj się! (“Take care!”)

- Uważaj na siebie! (“Be careful!”)

- Szerokiej drogi! (“Have a good/safe trip!”) (Literally: “Have a wide road!”)

- Napisz wiadomość jak dojedziesz! (“Text me a message when you arrive!”)

- Zadzwoń jak dojedziesz! (“Call me when you arrive!”)

Parents who are seeing their children off may say something like:

- Nie szalej! / Tylko bez szaleństw! (“Don’t go crazy!”)

D- When You Need to Excuse Yourself

Sometimes you need to leave the party before everyone else. Here are some phrases you can use to let your hosts know you have to get going:

- [Naprawdę] muszę lecieć! (“I [really] need to go!”)

- Będę się zbierać. (“I’ll be off!”)

- Niestety nie mogę dłużej zostać. (“Unfortunately, I can’t stay any longer.”)

- Pora na mnie! (“It’s time for me to go.”) [Literally: “It’s time for me.”]

If you’ve bumped into someone you know on the street, but don’t have time for a conversation, you can say:

- Miło się gada, ale muszę lecieć! (“It’s nice chatting with you, but I have to go!”)

- Miło się gada, ale jestem już spóźniony/spóźniona! (“It’s nice chatting with you, but I’m already late!”) [for a male and female, respectively]

E- Polish Goodbye Phrases for Phone Conversations

Politely ending a phone call in Polish is easy:

- Do usłyszenia! (“Chat soon!”) [Literally: “Until we hear one another again!”]

- No to do usłyszenia! (“Chat soon, then!”) [Literally: “Until we hear one another again, then!”]

You can also add a specific time reference to let the other person know when you’ll talk with them again:

- Do usłyszenia jutro! (“I’ll speak to you tomorrow!”)

- Do usłyszenia w przyszłym tygodniu! (“I’ll speak to you next week!”)

Do you have a cell phone? Learn all you need to know about Polish manners on the phone with PolishPod101.com.

F- Saying Goodbye in a Text Message

When you’re texting with someone and you’ve set an appointment to meet with them, you can use one of the expressions we’ve already covered in this article:

- Do zobaczenia!

- Do zobaczenia niedługo!

- Do zo!

You’d probably agree that knowing how to text is an important skill in the modern world. Boost your Polish technology vocab with our lesson.

G- Saying Goodbye to Someone Who’s Sick

When you bid farewell to someone who’s sick at home or at a hospital, it’s good manners to wish them good health. Here’s how you can do this in Polish:

- Wracaj do zdrowia! (“Get better soon!”)

- Szybkiego powrotu do zdrowia! (“I’m wishing you a speedy recovery!”)

- Mam nadzieję, że szybko wydobrzejesz. (“I hope you’ll get better soon.”)

To say goodbye, simply add one of the other phrases you’ve already learned, such as: Do zobaczenia!

Speaking of health, do you know how to talk about health concerns and explain your allergies in Polish? Also, if you’re moving to Poland, you may want to learn more about the Polish healthcare system.

H- Wishing Someone Good Luck

We all need a little luck sometimes, but there are life situations that call for it more than others. Such situations include taking an exam, going to a job interview, or performing in front of an audience. If you’re parting ways with someone who’s about to do something major, you can say:

- Powodzenia! (“Good luck!”)

- Połamania nóg! (“Break a leg!”)

- Trzymam kciuki! (“Fingers crossed!”)

You’re likely to hear these phrases if you study or work in Poland. Some Polish people are superstitious, though, so not everyone is going to thank you for wishing them luck. It’s believed that doing so may actually bring bad luck. In this case, you may hear the reply:

- Nie dziękuję! (“I’m not thanking you.”)

3. Final Thoughts

By now, you definitely have a better idea of how to say goodbye in Polish in a variety of contexts.

Remember to use these expressions whenever you can. Even if it’s the only thing you’ll say in Polish during a conversation, it’s still better than speaking only in English!

Which way of saying goodbye do you like the most? Let us know in the comments before you go.

Saying goodbye is an important skill, but on its own, it’s not enough for a smooth conversation. To boost your Polish speaking and comprehension skills, get your free account with PolishPod101 today.

Our website gives you access to countless language lessons and resources. Our recordings by native speakers will help you get the hang of Polish pronunciation in no time. You can also access your account whenever and wherever you want, thanks to our mobile apps.

Would you like to know more about our teaching methods? Check out our lessons and methodology page to find out more.

Happy Polish learning!

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents