It’s natural for a beginner to make mistakes in a new language. But fortunately, there are ways in which you can minimize them. To help you do exactly that, in this article, we’re going to discuss the ten plus most common Polish mistakes.

By understanding what kind of mistakes other students make, you can prevent yourself from falling into those same linguistic traps. For your convenience, we’ve put the most common Polish mistakes by English-speakers into groups.

Let’s get started.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- Pronunciation and Spelling Mistakes

- Vocabulary Mistakes

- Polish Grammar Mistakes

- Level of Formality

- Other Polish Mistakes

- The Biggest Mistake

- Final Thoughts

1. Pronunciation and Spelling Mistakes

The most common Polish mistakes that learners of different language backgrounds tend to make have to do with pronunciation and spelling.

A- Similar Spelling, Different Pronunciation

Certain consonants in Polish are particularly difficult for language-learners due to the fact that they’re written similarly to each other. Some students also feel that their pronunciation is relatively similar. The following letters and sounds are a source of common pronunciation and spelling mistakes for Polish-learners:

- s, ś, and sz

- c, ć, and cz

- dz, dź, and dż

Pay particular attention to how words with these letters are written when you’re reading something out loud. When writing down vocabulary, you need to be very careful as well, especially when you’re making notes of what you hear. In this case, check a given word in a dictionary to make sure you’re learning the correct form of it. Last but not least, listen to how native speakers pronounce words with these letters to train your ear.

B. Different Spelling, Same Pronunciation

The good news here is that people learning Polish as a foreign language are not the only ones with this problem. It’s quite common for native speakers to make this spelling mistake in Polish, too! This is because the letters in question are pronounced the same way, but spelled differently. However, a mistake that hits foreigners particularly hard is trying to pronounce double letter sounds as if they were separate letters.

Here’s another source of common Polish pronunciation mistakes:

- ch and h

- rz and ż

- u and ó

A good way to fight this problem is to learn vocabulary words along with their spelling and pronunciation. Reading plenty of articles and books can also minimize your chances of making these common pronunciation mistakes for Polish-learners.

- → Do you feel like you need more practice? Go to our lessons “An Alphabet Full of Polish Tongue Twisters” and “Polish Pronunciation Made Easy.”

2. Vocabulary Mistakes

There are many vocabulary items that are confusing for learners because certain ideas don’t exist in their native language. In the following sections, we’ll outline frequent errors in Polish that foreign learners tend to make.

A- Verbs of Motion

Polish verbs of motion are definitely among the top Polish-English mistakes. Have a look at the following verbs:

chodzić vs. iść

Both verbs can mean “to go” in English, which certainly doesn’t make your task any easier. However, what you should remember is the context in which we use them. Iść is used for activities that happen in a given moment, while chodzić is used for repetitive actions.

- Idę do pracy. (“I’m going to work.”)

- Chodzę do pracy pięć razy w tygodniu. (“I go to work five times a week.”)

Because chodzić refers to something that’s done frequently, it’s often accompanied by a plural form of the noun when talking about habits. Compare:

- Idziesz na spacer? (“Are you going for a walk [now]?”)

- Chodzisz na spacery? (“Is it your habit to take walks?”)

You’d also use chodzić to speak about “walking” as a general activity and iść to refer to “walking” in a given moment. For example:

- On nie może chodzić. (“He can’t walk.”)

- Czemu tak wolno idziesz? (“Why are you walking so slowly?”)

jeździć vs. jechać

Jeździć and jechać have a similar relationship as the previous pair of verbs. Both mean to go somewhere with a mode of transport. Jeździć is used for repetitive situations, and jechać for a description of something that’s happening in a given moment:

- Co roku jeździm nad morze. (“Every year, we go to the seaside.”)

- Dzisiaj jedziemy nad morze. (“Today, we’re going to the seaside.”)

How often do you go to the seaside? Learn how to talk about it with our lesson on how to express frequency.

Both verbs can also mean “to drive”:

- Ile lat jeździsz tym samochodem? (“How long have you been driving this car?”)

- Jadę samochodem, nie mogę rozmawiać. (“I’m driving, I can’t talk.”)

B- Imperfective and Perfective Verbs

Polish verbs have an aspect and are divided into perfective aspect and imperfective aspect verbs.

Perfective verbs focus on completion of an action, so they’re associated with the past and the future. Imperfective verbs, on the other hand, focus on the fact that the action is being performed.

The difference isn’t obvious to many foreigners, which makes it a common source of Polish grammar mistakes. Have a look at the following pairs with examples to see the difference:

kupować (imperfective) vs. kupić (perfective) – “to buy”

- Kupowałam pierogi, kiedy zadzwoniła mi komórka. (“I was buying pierogi, when my phone rang.”)

- Kupiłam pierogi. (“I’ve bought pierogi.”)

Go to our lesson “10 Polish Foods” to learn what else you can eat in Poland.

śpiewać (imperfective) vs. zaśpiewać (perfective) – “to sing”

- Śpiewam w chórze. (“I sing in a choir.”)

- Zaśpiewam ci piosenkę. (“I will sing a song for you.”)

jeść (imperfective) vs. zjeść (perfective) – “to eat”

- Jem obiad. (“I’m eating lunch.”)

- Zjesz obiad? (“Will you eat lunch?”)

C- Talking About Age

In Polish, you should use the verb “to have” (mieć) to speak about your age. This is different from English, where you use the verb “to be,” making this one of the most common mistakes in Polish made by English-speakers. Compare:

- Mam 32 lata. (“I’m 32 years old.”)

- Ile masz lat? (“How old are you?”)

Are you still not sure how to talk about your age? Go to our “Polish in three minutes“ lesson about this topic.

D- Knowledge Verbs in Polish

There are three different verbs that refer to knowledge in Polish: umieć, wiedzieć, and znać. As luck would have it, they all translate to the English verb “to know,” and therefore, they’re among the most typical Polish mistakes made by foreigners.

umieć

We use this verb to talk about skills, such as:

- umieć liczyć (“to know how to count”)

- umieć śpiewać (“to know how to sing”)

- umieć czytać (“to know how to read”)

wiedzieć

We use this verb to talk about knowledge in more specific situations:

- Nie wiem, co masz na myśli. (“I don’t know what you mean.”)

- Nie wiem, czy to prawda. (“I don’t know whether it’s true.”)

- Nie wiem, ile ma lat. (“I don’t know how old he is.”)

znać

We use this verb to talk about people we know, languages we speak, and when a noun follows the verb directly:

- Nie znam jej męża. (“I don’t know her husband.”)

- Nie znam angielskiego. (“I don’t know/speak English.”)

- Nie znam prawdy. (“I don’t know the truth.”)

3. Polish Grammar Mistakes

Many of the top Polish-English mistakes have to do with grammar elements that are confusing for English-speakers. Following is a list of Polish mistakes you should always try to avoid!

A- Expressing “Going to” in Polish

Some English-speakers try to express the idea of “going to” with verbs of movement. The confusion has to do with the fact that you can say:

- Idziemy na basen. (“We’re going to a swimming pool.”)

What’s important to remember is that the meaning of this sentence has to do with the verb iść (“to go”).

- Planujemy pójść na basen. (“We’re going to go to a swimming pool.”)

To refer to planned actions and express “going to” for future events, you should use other verbs, such as planować (“to plan”) as in the example above.

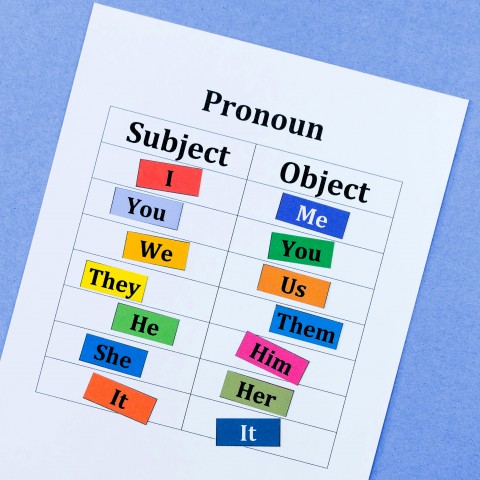

B- Gender Agreement

Lack of gender agreement is among the most common Polish grammar mistakes. In English, nouns do not have gender, so the mere concept is alien to English-speakers. In Polish, though, each noun has gender and it always has to be in agreement with the adjective used to describe it:

- mądra kobieta (noun, feminine) – “a smart woman”

- mądry człowiek (noun, masculine) – “a smart human being”

- mądre dziecko (noun, neuter) – “a smart child”

The agreement also takes place with other parts of speech that are modified, such as pronouns:

- taka mądra kobieta (noun, feminine) – “such a smart woman”

- taki mądry człowiek (noun, masculine) – “such a smart human being”

- takie mądre dziecko (noun, neuter) – “such a smart child”

The gender agreement is also affected by number. Compare singular and plural:

- mądra kobieta (singular) / mądre kobiety (plural)

- mądry człowiek (singular) / mądrzy ludzie (plural)

- mądre dziecko (singular) / mądre dzieci (plural)

To learn more about the topic of gender, familiarize yourself with our lesson “The Secret to Understanding Polish Noun Gender.”

C- Case Agreement

The Polish language has seven different cases, and Polish noun cases are a source of many common Polish grammar mistakes. Students who struggle with this particular grammar concept the least are speakers of other Slavic languages.

- Ala ma kota. (“Ala has a cat.”)

The proper noun “Ala” is in the nominative case here. If you decide to add an adjective or pronoun to modify a noun, you’ll have to use the nominative case for it. Case agreement is done in conjunction with gender agreement:

- To sympatyczna dziewczyna [feminine noun]. (“She’s a nice girl.”)

Would you like to learn more Polish adjectives? Check out our lesson about high-frequency adjectives.

The same process takes place for pronouns:

- Moja mama [feminine noun] ma dwa psy. (“My mother has two cats.”)

This is true for all cases, and it’s something you should always keep in mind when forming sentences in Polish. A good way to practice is to create simple sentences to make sure you understand when to use which case. This process is much more effective under the eye of a teacher. You can gain access to one through a Premium PolishPod101 membership.

This sums up the most common Polish grammar mistakes. Now, it’s time to move on and discuss another common mistake in Polish, namely, the level of formality.

4. Level of Formality

One of many important mistakes in Polish to avoid are related to the level of formality. In English, you’re used to using “you” with almost everyone. But Polish recognizes two types of “you,” the formal one and the informal one.

The informal version, ty, is used among friends, family members, and people of the same age. It requires the second person singular form of the verb:

- Jak się masz? (“How are you?”)

The formal version—pan for a man or pani for a woman—uses the third person singular. We use it with people who we don’t know, unless they’re children or teenagers. We can also use it if the context seems to call for it. Here are two examples:

- Jak się pani ma? (“How are you, Ma’am?”)

- Jak się pan ma? (“How are you, Sir?”)

To be on the safe side, use formal Polish. Being too formal is certainly better than being overly familiar.

5. Other Polish Mistakes

Other common Polish mistakes have to do with question formation and negation.

A- Forming Questions

It’s easy to make a mistake in Polish when forming questions. This is because, in the spoken language, questions are simply indicated by the change of intonation. Many other questions, even in writing, get the same word: czy. In English, on the other hand, the question word differs depending on the tense:

- Czy masz ochotę na kawę? (“Would you like a coffee?”)

- Czy Marcin kupił jajka? (“Did Marcin buy eggs?”)

- Czy mam rację? (“Am I right?”)

Of course, Polish has words for “who” (kto), “what” (co), and so on. Want to learn more? See our lesson on the 10 questions you should know.

B- Negation

Polish allows double negation, leading to many Polish-English mistakes because it seems particularly unnatural to English-speakers. Have a look at the following examples:

- Nikogo nie widzę. (“I don’t see anyone.”) – Literal translation: “I don’t see no one.”

- Nigdy tego nie zrobię. (“I’ll never do it.”) – Literal translation: “I’ll never not do it.”

- Marek niczego nie czyta. (“Marek doesn’t read anything.”) – Literal translation: “Marek doesn’t read nothing.”

6. The Biggest Mistake

The biggest mistake in Polish is…not practicing the language. Perfection is something many of us aspire to, but it’s impossible to achieve. You should simply try your best and keep practicing. To make a mistake in Polish isn’t a sign of weakness, but simply an indication that you’re learning. Using the language is the only way to get better at it!

7. Final Thoughts

Today, we’ve discussed the most common Polish language mistakes. Thanks to this article, you’ll be able to avoid the top Polish-English mistakes!

Before you go, remember to let us know in the comments section which of these common mistakes in learning Polish bother you the most!

Don’t stop your learning journey here. Continue improving your Polish skills with PolishPod101. We have countless resources for you to learn with, and all of our audio and video lessons featuring native speakers will help you avoid common pronunciation mistakes in particular. Get your lifetime account today!