Many people come to Poland to learn Polish or study. Regardless of the level of education you’re trying to obtain, Polish classroom phrases will come in handy. It’s also good to know them for cultural reasons, for instance, to understand better what’s happening in Polish movies or series. Of course, it’d also be very useful to know them for general Polish language learning.

The knowledge of the most common Polish phrases used in the classroom is also very helpful in understanding more about the country’s culture. The way that teachers and students interact allows you to better understand the levels of formality in the Polish language.

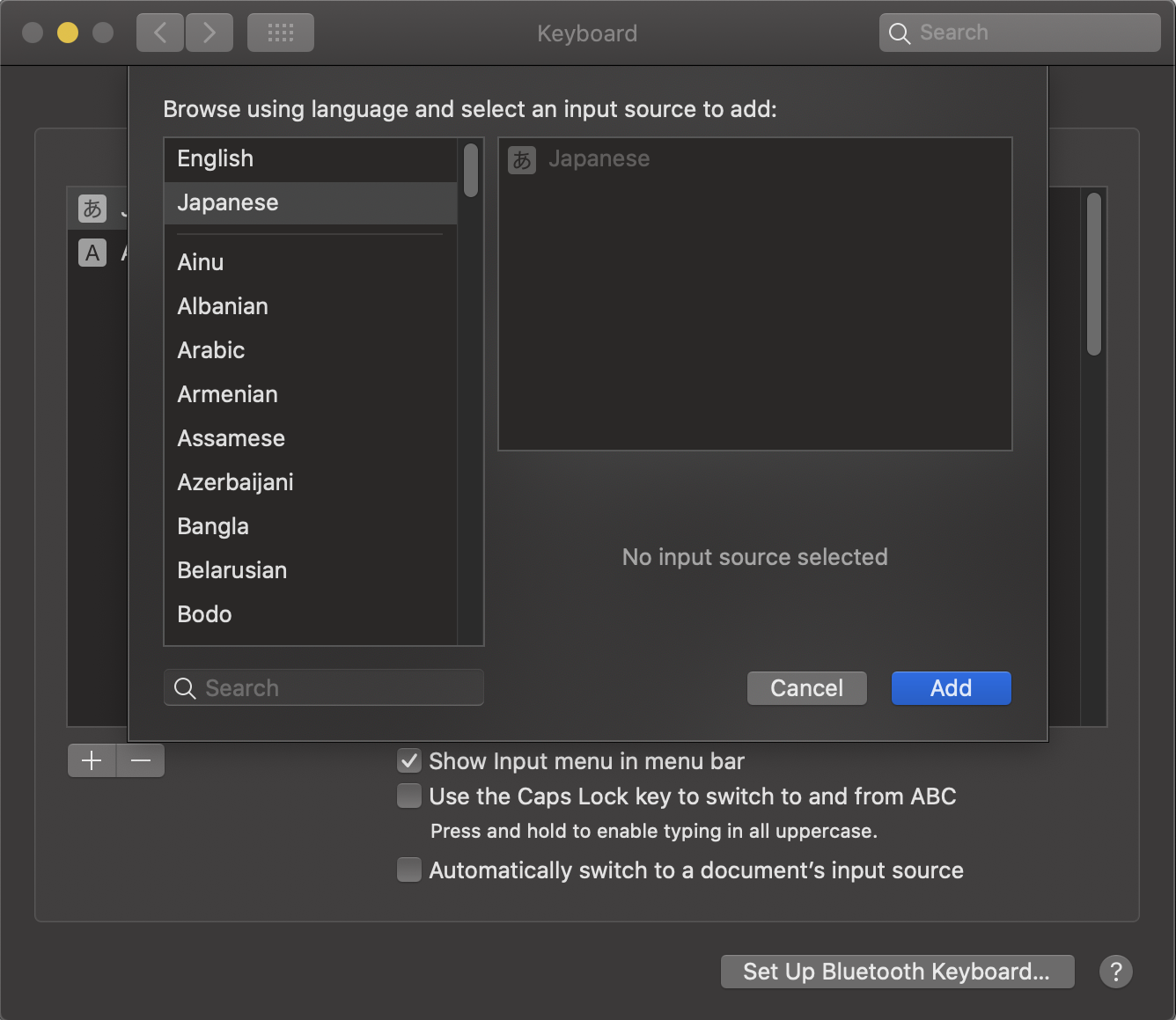

Please note that Polish is a gendered language, and genders will be marked in this blog post as follows:

- m – masculine

- f – feminine

- n – neuter

Without further ado, let’s discuss the most common Polish phrases used in the classroom!

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- Basic Classroom Greetings

- Understand Instructions from Teachers

- Ask for Clarification from Teachers and Classmates

- Explain Absence and Tardiness

- Talking About Favorite Subjects

- Check for School Supplies

- Final Thoughts

1. Basic Classroom Greetings

Greetings are a part of everyday life. When you live in Poland, the skill of saying hello no matter the time of day can come in very handy. In the classroom environment, there are certain special greetings you should memorize:

- Dzień dobry. – Good Day.

You can simply say Good Day when entering the classroom. However, people, especially children, use a special greeting to show their respect for the teacher:

Dzień dobry, Pani (Profesor). – Good Day, teacher. (literally: Mrs Professor)

Dzień dobry, Panie Profesorze. – Good morning, teacher. (literally: Mr Professor)

Dzień dobry, Panu. – Good morning, teacher.

This form is also used at higher learning institutions. It’s worth noting that the required level of formality will depend on the personal preferences of a lecturer or rules at a given institution.

- Cześć! / Siema! – Hi!

Ex. Siema is a slang word for cześć.

To say “hi” to fellow students, we use the expressions above. Both can also be used to say “bye.”

- Co tam? – What’s up?

We can also ask someone how they’re doing informally by using the above expression. - Do jutra! – See you tomorrow!

Another informal expression used to say goodbye only.

Now that you know how to say hello in different ways, you may also want to learn three ways to say “Bye” in Polish. All of them are basic Polish phrases.

2. Understand Instructions from Teachers

There are a number of instructions teachers use to communicate with their students. Traditionally, teachers in Poland require a fair amount of obedience. What can look harsh to an English speaker is related to the cultural straightforwardness of Polish, where words of politeness aren’t always used.

- (A teraz) słuchajcie uważnie. – (And now) listen carefully.

A phrase often used by teachers before important details of a lesson come. - Proszę o ciszę! – Be quiet, please.

Cisza! – Silence!

Both phrases could be used by Polish teachers to regain control of a classroom where children or students are behaving badly. - To bardzo ważne. – It’s very important.

Classroom phrases for teachers in Polish differ from teacher to teacher, but many like to underline the importance of something in this way. - Nie ma się z czego śmiać. – There’s nothing funny here.

Polish children can laugh when uncalled for like any other children. That’s why Polish teachers will sometimes use this expression. - Wyciągamy karteczki. – We’re taking out pieces of paper.

Polish classroom words and phrases also include the ones related to tests. Many tests in Polish schools are announced, and then they’re called klasówka. When teachers want to check whether students are learning systematically, they also prepare unannounced tests called kartkówka.

- Any questions? – Czy są jakieś pytania?

This isn’t a request per se, but it’s a phrase worth noting as teachers often ask them after concluding a topic or before finishing a lesson.

Classroom phrases for teachers in Polish, include the top 5 pet phrases. Check them out with our lesson. You can also learn more about learning strategies with the power of a good Polish teacher.

3. Ask for Clarification from Teachers and Classmates

If you’re a foreign student, you may not understand everything that a teacher or classmate asks from you. That’s why our Polish classroom phrases for students include asking for clarification from others:

- Nie rozumiem. – I don’t understand.

Example:

A: Jaka jest Pańska godność? – What is your name, Sir? (literally: What’s your dignity?)

B: Nie rozumiem. – I don’t understand.

- Czy może Pan/Pani powtórzyć? – Can you repeat that, Sir/Madam?

Czy możesz powtórzyć? – Can you repeat that?

Example:

A: Jak leci? – How is it going?

B: Nie rozumiem. Czy możesz powtórzyć? – I don’t understand. Can you repeat that?

- Chciałam zgłosić nieprzygotowanie. – I wanted to say I’m not prepared.

In Polish schools, some teachers ask children to answer questions orally and be graded while standing in front of the classroom. The questions usually revolve around what was discussed during the last few lessons. A student is allowed to tell the teacher that they’re not prepared a few times during the term. However, they need to say it before the teacher asks them to answer questions. When a student wants to express that, they use the phrase above.

- Mam pytanie. – I have a question.

When you want to ask a question to a teacher you usually raise your hand to get their attention before you do that. - Co powiedział nauczyciel? – What did the teacher say? (when the teacher is a man)

Co powiedziała nauczycielka? – What did the teacher say? (when the teacher is a woman)

If you don’t understand what the teacher said, you can ask about that. Of course, there are slang words that children and teenagers use for teachers such as belfer (m) / belferka (f) or facet (m) / facetka (f).

4. Explain Absence and Tardiness

Polish children, teenagers, and older students are great at coming up with excuses for their absence and tardiness. That’s something that students seem to have in common all around the world. Here are some Polish classroom words and phrases that can come in handy when you need an excuse yourself:

- Źle się czułem (m) / czułam (f). – I wasn’t feeling well.

Example: Nie przyszłam na zajęcia, bo źle się czułam. – I didn’t come to class, because I was feeling unwell. (when the speaker is a woman)

Nie przyszedłem na zajęcia, bo źle się czułem. – I didn’t come to class, because I was feeling unwell. (when the speaker is a man)

- Przepraszam za spóźnienie, uciekł mi autobus. – Sorry I’m late. I’ve missed the bus.

Przepraszam za spóźnienie, zaspałem (m) / zaspałam (f). – Sorry I’m late. I’ve overslept.

Przepraszam za spóźnienie, straciłem (m) / straciłam (f) poczucie czasu. – Sorry I’m late. I’ve lost track of time.

- Nie mam pracy domowej, bo zjadł mi ją pies. – I didn’t bring my homework, my dog ate it.

Of course, some students would try this excuse. However, telling the teacher that one is unprepared is also an option to avoid consequences, as long as the student hasn’t used up their limit. - Przepraszam, nie zrobiłem (m) / zrobiłam (f) pracy domowej. – I’m sorry, I didn’t do my homework.

- Zapomniałem (m) / Zapomniałam (f) książki / zeszytu. – I’ve forgotten my book/notebook.

What excuses did you use at school, or were you too cool for school and played truant often? Let us know in the comments section.

5. Talking About Favorite Subjects

There are some people who simply don’t or didn’t like school. But even they usually had at least one favorite subject. The most common Polish phrases used in the classroom include those to speak about people’s preferences in that respect:

- matematyka – math

- chemia – chemistry

Ex. Jestem dobra z matematyki i chemii. – I’m good at math and chemistry.

- fizyka – physics

Ex. Nie rozumiem fizyki! – I don’t understand physics. - historia – history

Historia nie jest trudna, ale jest dużo dat do zapamiętania. – History isn’t difficult, but there are many dates to remember. - (język) polski – Polish

Polski jest fajny poza gramatyką. – Polish is cool, apart from the grammar. - (język) angielski – English

Ex. Angielski jest łatwy. – English is easy.

- geografia – geography

Ex. Geografia Europy jest skomplikowana. – European geography is complicated. - biologia – biology

Biologia nie jest obowiązkowa w mojej szkole. – Biology isn’t obligatory at my school. - WF (wychowanie fizyczne) – PE (physical education)

Lubię sport, ale nie lubię WFu. – I like sports, but I don’t like PE. - Mój ulubiony przedmiot to [subject]. – My favorite subject is [subject].

Ex. Mój ulubiony przedmiot to (język) polski. – My favorite subject is Polish. - Nie lubię [subject]. – I don’t like [subject].

Ex. Nie lubię fizyki. – I don’t like physics. - Jestem dobry (m) / dobra (f) z [subject]. – I’m good at [subject].

Jestem dobry z matmy. – I’m good at maths.

Ex. Matma is a slang word for matematyka. - Jestem słaby (m) / słaba (f) z [subject]. – I’m bad at [subject].

Ex. Jestem słaby z WFu – I’m bad at PE. - Mam dobre / złe oceny z [subject]. – I have good/bad grades in [subject].

Ex. Mam złe oceny z geografii. – I have bad grades in geography.

If you’d like to learn more Polish vocabulary on this topic, here’s a lesson on talking about school subjects in Polish. You may also want to learn more about the education system in Poland.

6. Check for School Supplies

It’s equally important to be able to speak about school supplies. Some of them are similar to the ones you can find in the office. Here’s a list of Polish classroom phrases for students:

- zeszyt – textbook

- książka – book

- długopis – pen

- pióro – fountain pen

- ołówek – pencil

- plecak – backpack

- kalkulator – calculator

- Zgubiłem (m) / Zgubiłam (f) mój (m) / moje (n) / moją (f) [supply]. – I’ve lost my [supply].

Here the choice is between the form for a male and female speaker, and then the form of the word “my” has to be in agreement with the gender of the noun used.

Ex. Zgubiłem mój długopis. – I’ve lost my pen. (said by a man)

Zgubiłam moje pióro. – I’ve lost my fountain pen. (said by a woman)

Zgubiłam moją książkę. – I’ve lost my book. (said by a woman)

- Potrzebny mi nowy (m) / nowa (f) / nowe (n) [supply]. – I need a new [supply].

Ex. Potrzebny mi nowy kalkulator. – I need a new calculator. - Widziałeś (m) / widziałaś (f) mój (m) / moje (n) / moją (f) [supply]? – Have you seen my [supply].

Ex. Widziałaś mój plecak? – Have you seen my backpack? (When a woman is asked).

Note that our list of Polish words and phrases doesn’t have a name for uniform (mundurek szkolny). That’s because they’re not obligatory in Poland.

Do you know by now what’s in your school bag? If you still have doubts, review our lesson on this topic by clicking on the link and learning even more basic Polish phrases.

7. Final Thoughts

We hope you’ve enjoyed learning about all the Polish classroom words and phrases. They’ll come in handy whether you’re taking a Polish course, attending a Polish school, or living in Poland. Perhaps it made you remember the times when you were at school yourself.

Knowing classroom phrases for teachers in Polish, as well as these for students, is just the beginning of the road. To truly speak the language, you should use a platform that has countless recordings from native speakers and a large Polish lessons database to help you learn Polish vocabulary and much more. PolishPod101 is exactly that kind of platform. Try it out today and learn Polish with us!

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents